D&C 20 is often referred to as the Constitution of the Church, and, like any constitution, it can be treated as a reference manual for its instructions to members and officers from verses 37 through 84 rather than for the doctrinal underpinnings it offers in its early verses.

Its early verses contains the earliest published retelling of the First Vision and Moroni visits, albeit in summarized and oblique form, and then walks the audience of 6 charter members and 30-some other attendees through a concise doctrinal tour de force dismantling several points of doctrinal disagreement among Christians.

Two quick notes before we do the analysis:

1. This borrows substantially from Jared Halverson's Unshaken Saints podcast on this topic.

2. Before thinking through a theological disagreement, it serves to remind ourselves that people are not institutions, and creeds are not fellow humans. While it's important to engage ideas deeply, it's often completely inappropriate and counter to the Spirit's manner of persuasion to attempt to defeat a holder of beliefs contrary to ours in some sort of competition or debate. The person who holds the beliefs deserves love and respect. They deserve for their beliefs to be honored for all the good they do, and for their person to expect invitations to add truth to them, not challenges that undermine them. I'm not always as adept as I would wish at separating these two functions--the ideas attract me and call for direct intellectual engagement as ideas without me always choosing the most gentle or most apt strategic path to persuasion on the interpersonal level. I begrudge no one their beliefs, and wish to persecute no one for differences of belief. And I claim the privilege also of worshiping God as my own conscience dictates, allowing all my interlocutors the same privilege. What I offer below is sharing, even when sometimes sharp, and I honestly hope any of my Presbyterian friends and family will take honest criticism in the spirit of brotherhood and desire for them to open, rather than close their minds to the more correct ideas I'm presenting.

Since the early 1500s, the French priest Jean Calvin has had an important influence on Protestant theology. Presbyterians principally, but also Episcopalians, Baptists, Anglicans and Methodists of some stripes either conform to some of his distinct "reform" theology, or have to reckon with it in delineating their distinction from it, as do Lutherans and Arminian theologians. His "five points" of soteriology were in ascendancy in the western frontier of the United States such as it was in Joseph Smith's day (meaning upstate New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and points south, but barely more western). So the following doctrine, received in this section as the text of a revelation, but which is also a distillation of the Book of Mormon's "fullness of the Gospel," must have created a new space for a return to the Biblical text on which Calvin's five points purport to be drawn--a new point of comparison, a new perspective from which to judge the truth.

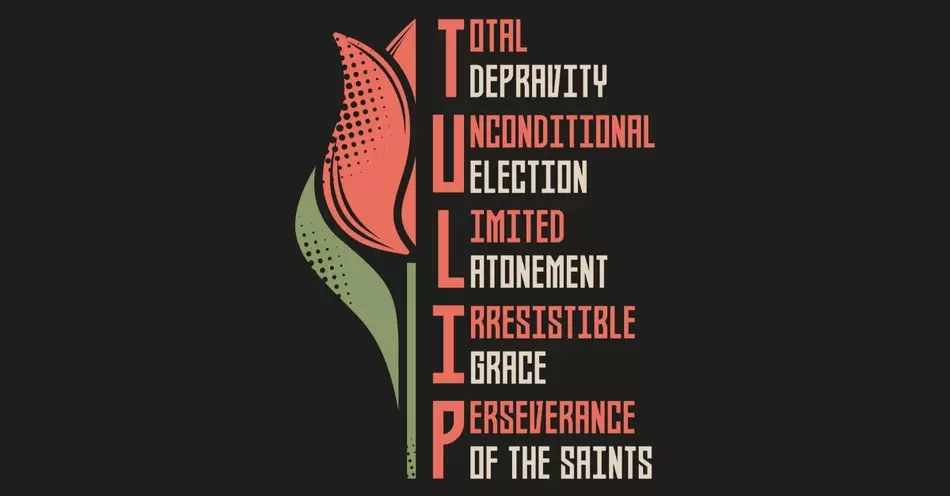

Summarized in the acrostic TULIP, these five point find counterpoints in Smith's 1830 revelation.

T for total depravity.

Calvinists hold that there is no impulse for good in the nature of humans. For them, the human family has been enslaved to sin by the fall of Adam, and inherits from the conditions he caused the impossibility of not just saving themselves from sin, but from any choices that would even incline them toward repentance, good works, virtue, or any other Godly quality. While this philosophy provides for an abundantly healthy skepticism of human motivations, and therefore prevents many abuses of power (or helps its adherents prepare adequately against them), it can't apply without evacuating the concept of moral agency.

Smith's take, from verse 25 provides a clue to a corrective:

"as many as would believe and be baptized in [Christ's] holy name, and endure in faith to the end, should be saved"

The word "would" does all the work and makes all the difference here. Humans do have a will all their own. and while God's omnipotence will have its full will implemented on Judgment Day, there is a space He has created for a temporary liberty to defy Him. This theoretical power to run contrary to His will, even temporarily, creates the conditions by which humans have the capacity not to, even in this fallen world. And it also creates the conditions for our own responsibility to choose the right, such that our punishments for not doing so fully and justly rest upon ourselves. The act of will to believe in a Savior and then choose to act accordingly is the Good News that His Gospel signifies. We are not totally depraved, just fallen. We are not off the hook, but accountable. We are not predetermined puppets, but real moral agents.

U for unconditional election.

God's omnipotence and omniscience has implications for a Calvinist. A Being of such power that He can't fail and of such intelligence that He knows the eternities beforehand means that His mercy extends only to a select few, and that no merit, faith, or virtue on their part--no condition they control or belong to--has any role in their selection. He predestines the elect, and they are powerless to reject His gracious election.

While this concept does deep deference to God, and again places healthy distrust on one's own virtues, merits, and faith, from the outside it appears utterly circular--if nothing you did puts you inside the group of the "chosen" then when you make choices that show you can't be one of the "elect" the only explanation available is that you must not have been "truly" elect in the first place.

What makes a person "elect?" according to the Restored Gospel? What "saves?" What grants "justification" and then "sanctification?" It's still the grace of God. But notice how it's phrased here in verse 29:

"all men must repent and believe on the name of Jesus Christ, and worship the Father in his name, and endure in faith on his name to the end, or they cannot be saved in the kingdom of God."

Notice how it's the responsibility of the "men" (all humans in 1830s parlance) to take on certain acts and make certain choices, and then to stick with them. God's grace enables all of that--we can agree with the Calvinists there--but His grace also grants to each of us a will, and that will is accountable to make those choices, perform those acts, and hold firm in an all-in commitment that is matched in heaven, but which is ours to initiate and develop with that omniscient and omnipotent partner who takes our burdens on Himself when we are yoked with Him.

L is for limited atonement.

However incomprehensible to the human understanding the Savior's sacrifice was, Calvinists believe that it had a target, and therefore a scope. Its effect was intended for the "elect" and since God never misses His target, it was therefore perfectly and infallibly only for them. We may all get benefits from that supreme act of mercy and sin-coverage, but not everyone benefits fully.

For these Calvinists, who can never quite be sure, this concept paradoxically both makes them shrug off personal failures in case they just aren't the elect, and makes them intensely pious in case they are. So while they are prone to consistency in humility and gratitude for a Savior that saves the elect from their depravity, and they generally live lives of service and faith, their philosophy tends to allow them an out for their excesses.

Section 20:31, on the other hand not only notes above that "all men" must and can repent, and hold on in faith, but also offers the following:

"sanctification through the grace of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ is just and true, to all those who love and serve God with all their mights, minds, and strength."

Again the determiner "all" is doing all the work: there is no one exempt from the responsibility of aligning with the conditions of acceptance of Christ's sanctifying grace--the application of their own might, mind, strength, and love.

I is for irresistible grace.

One other corollary of a god-concept so sovereign is that it can overpower the human will, and that therefore it must and will. No one who is among the elect has sufficient power to forestall the effects of his grace. If you're a recipient, no sin, no resistance can prevent your salvation. To be fair, Calvin's approach to God's sovereignty as continually unlimited, even in mortal spaces, doesn't equate to force. Instead, with a subtle distinction, he posits that the Holy Spirit overcomes whatever resistance an "elect" may have by its own forms of persuasion until God eventually wins over the sinner.

The subtle distinction between outright force and gentler force holds sway with Reformed congregations in which testimonials about how God's influence turned around the path they were on abound. And yet, the philosophy, pursued to its end, at its logical extremities, does ultimately remove agency from humans, and both prevents them from imputing growth toward the model of Christ to their own choices and lets them off the hook for their bad choices.

The above quote also points to an investment by each agent, who must turn their hearts, no matter the material and spiritual obstacles in the way, to the Lord with all their might, mind, and strength. Under the Restored Gospel, saints are just as likely to impute to God's grace the gifts of energy, intellect, and muscle He grants unto them to accomplish His commandments, but they understand the purpose of the gift of moral agency to be necessarily their own, because in no other way can they grow and have the growth be their own.

P is for perseverance of the saints.

With God's sovereignty able to overpower the human will, and with the omniscience pre-selecting the few predestined for salvation without their knowledge, the concept of a fall from grace is a logical impossibility to Reformed theologians. This brings us back to the tautology of labeling a relapsing sinner as falsely elect in the first place.

In response, on the day of the Restoration of His church, the Lord inspired verses 32-34:

"But there is a possibility that man may fall from grace and depart from the living God; Therefore let the church take heed and pray always, lest they fall into temptation; Yea, and even let those who are sanctified take heed also."

When the biblical pattern of mantic revelation to a current-day prophet factors in, it becomes more and more clear what the Savior meant when He told a farmboy willing to ask the question of which church to join that he was to join none because their creeds were an abomination to Him. It's not that their faith is bad or insincere. It's not that their devotion and piety are unacceptable. Quite the contrary--we should all recognize the good that people do, and that their motivations count. But to the Lord, who must insist on a purity of doctrine because being off by even a degree makes a valued son or daughter miss the mark in far-off eternity, any impurity destroys infinite potential. He wasn't judging people, He was inviting all to add to their faith, or refine the direction of their faith. As in the times of the Pharisees whose piety was acceptable when it wasn't false, and whose service was acceptable when it was from the heart, Calvinists have a credo that prevents them from sound, contextualized interpretation of only a very few, but very important scriptures.

And it takes a Restoration, not a "reform" to correct them. The Constitution of the Church was not revealed as a rebuttal to Calvinism. In none of the verses I've cited does Joseph Smith engage in exegesis, biblical reference, or homiletics. There is no debate presented, no explanation of how to ground doctrine in the Bible or in the Book of Mormon--the only two books of Scripture available at the time--but rather a simple, positive statement of what salvation consists of, how to tap into Christ's grace, and what a walk in grace looks like. God revealed it. It comports with all prior scripture, just not one credo's take on scripture. Christ saves, and He wants to save us all, so He commands us to use our will to choose Him out of love just as He chooses us in His perfect love.

No comments:

Post a Comment