I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine.

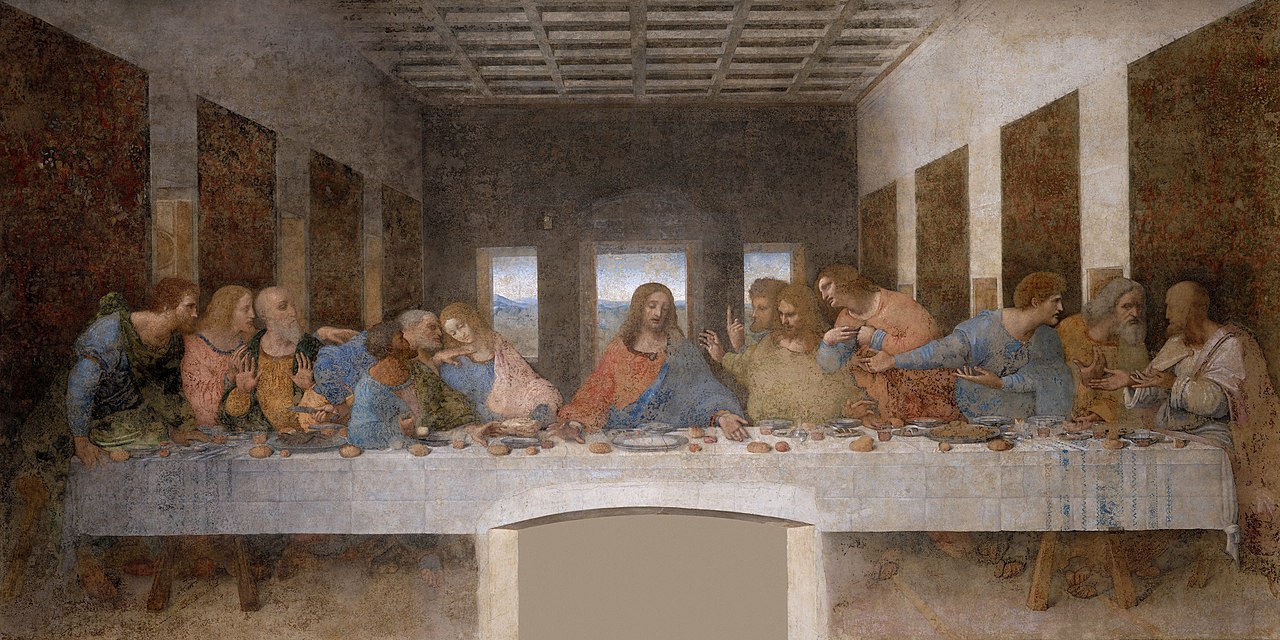

Whenever God has had a people on the earth, there has been both a symbolic and a real connection between place and covenant. Adam and Eve lost their garden of Eden, but knew that covenants with the prophesied Savior would restore them and their posterity to a place of peace. Noah's flood prepared the earth for a covenant people; Melchizedek's city of peace--Salem, forerunner of less ancient Jerusalem--was a refuge for the righteous; Abraham first, and Moses a half millennium later were both promised a promised land. Jaredites, Lehites, and Mulekites from the Book of Mormon record all were guided by God to a promised land as well. All of the ancient prophets involved understood that covenant living under Christ required several elements: a law revealed from heaven connecting behavior with principles, administered by authority, welding the spiritual with the economic, with the political, with the social, and with the psychological. Individuals had to covenant individually, and had to conform to a God who asked them to love others as He loves them--in a self-sacrificial manner--so that the group identity ensured horizontal equality, and oneness in vertical orientation.

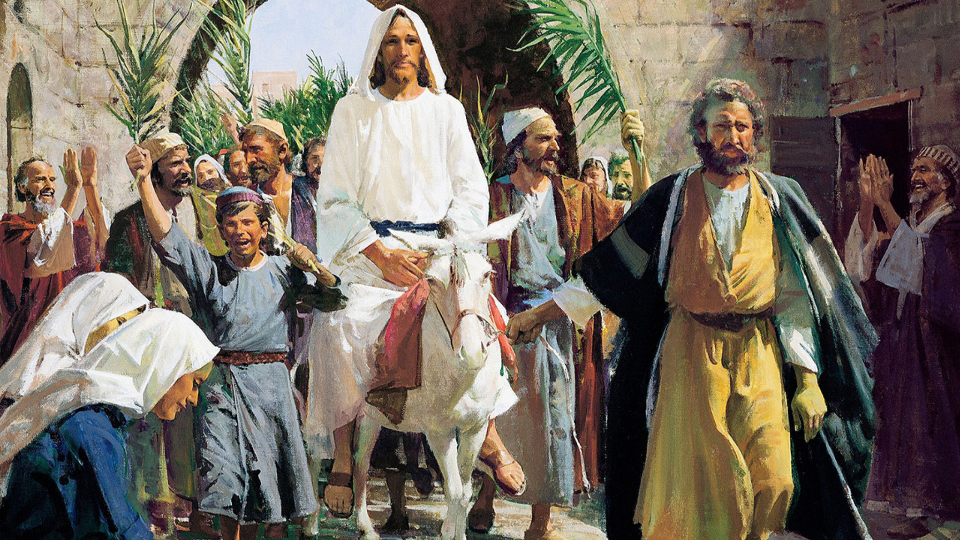

Jesus Himself also taught the principles of a Zion-like society, inaugurating the Church as its vehicle, with love as its key. His New Testament (more accurately rendered New Covenant) teaching was a love of one another, the Greek of which suggests love of believers for other believers, not necessarily a generalized love with no distinction. After His resurrection, He revealed further implementation instructions to His apostles, who instituted an economic order as a component of the spiritual life of the Church--a practice of having all things in common (Acts 2:44-45), in which property was submitted to the church, which administered to needs through inspired redistribution of pooled resources.

As Joseph Smith had begun to receive revelation on textual corrections to the King James Version's biblical text, he had recently refined text from Genesis, later separated into the Pearl of Great Price book of Moses, to broaden the lessons available from the original Zion--Enoch's city. Until that revelatory work, connecting the term Zion to a city that predated David's capture of Jerusalem is available only through extra-biblical sources: non-canonical rabbinical, apocryphal, and pseudepigraphal. These flesh out Enoch's connection to a group of 800,000 who refused to leave as Enoch was taken up to heaven in a chariot of fire, granting a wider pseudo-historical dimension to the symbolic meanings the "city of God" gathered throughout the Psalms, Isaiah, and other poetic and prophetic Old Testament writings which saw Zion as Jerusalem, not the name of a previous city of God. The broader Christian world readily connected Zion past Jerusalem, extending the metaphor to cover the "people" of God occupying a symbolic, non-literal space. But now, with this Doctrine and Covenants section, early saints of the Restored Gospel could re-frame the terms, and incorporate the gathering of Israel literally back to the physical Jerusalem with a longer pattern--a gathering to a more abstract set of potential lands of promise. Before Jerusalem's Zion, there was Enoch's, and now there could be maybe Kirtland!

With these newly revealed elements freshly on his mind, the biblical pattern became clearer, and it must have been less surprising to Smith than to the early restored Christians he led when the revelation came down before the organization's first birthday back on earth. There needed to be a specific place of gathering, a set of endowments of "power from on high", and a new ordering of social and economic affairs packaged together with the collective identity of becoming the covenant people. Learning the detail that Zion wasn't merely a metaphor for an eternal gathering place, but was a repeated "promised land" concept that could be brought about in the material world as much as in the spiritual one, the "wisdom" that every man should "choose for himself" whether and how to implement was to "assemble together at the Ohio" where a small, but robust contingent of new converts awaited (D&C 37:3-4).

The gathering commandment exposed some more than others--those with deeper economic roots and more complicated finances would have to sell, rent, or abandon property. Property that was likely hard won, recently cleared, and barely profitable for sale over winter months. It placed more of a material burden on those with more stake in growing where already planted, and comprised a test of faith for the fledgling few.

And this inequality of burden was a central part of what the text of Section 38 addressed. The Lord, through his prophet, shared for the first published time that Enoch's city of Zion was taken up into His bosom, as are all who covenant to become clean through His blood. And as the saints were to assemble in Ohio, there was an implicit parallel drawn (that many may have mistaken for a direct parallel) between the Kirtland where they eventually built a temple, and the kind of "promised land" that the scriptural pattern that Enoch's city was the newest best example of could apply to them. This would require preparations, sacrifices, and personal work, but it would have the effect of blessing those who sacrificed and would also have the effect of physically separating the world--worthy of judgment as it was--from the righteous seekers of relationships of oneness with Christ.

The problem is that oneness with Christ requires oneness with His attitudes, and those hit the "haves" with a double whammy: not only does He have a positive compassion for the poor, He negates privilege and status through a negative flattening--being no respecter of persons. Those who He has blessed with material abundance are under a disproportional burden, and a paradoxical commandment: turn more over to Him, and prosperity will continue more abundant. Principles have no proportions in their application, even if they sometimes do in their impact, and being no respecter of persons, like the Lord, means letting Him give the laws and the means, turning over both will and property in faith.

Now don't get me wrong--private property is still a valid principle, and being willing to deed it all away isn't the same thing as a vow of poverty. Sufficient for sustenance and increase is to be deeded back, so that individuals are responsible for their effort in magnifying their stewardship. But the stewardship principle is the operative one here: all property is the Lord's, and the faithful will do better with the sacred trust He allows them to invest than they would if it were their own property. Stewards tend to act wisely, and actively, yet humbly, with gratitude for temporary privileges form their Lord, and in the long view of all the stakeholders, rather than the narrow short-term interests they might if they were owners.

Zion requires more than membership, it requires that each member of the group consecrate themselves--uphold high standards that prevent dragging the whole group down, and contribute actively with a high degree of care for one another. And this group of new saints were not ready. But they were being led toward readiness. There's no way they could have known what sacrifices their consecration would require, but they could begin to prepare for it through obedience--moving to Ohio--listening to parables, instructions, and teachings pointing them toward economic equality, toward personal worthiness, and toward selfless service in following Christ's pattern. They didn't yet know that Zion was the "pure in heart," but their actions in heed of the prophet, in self-denial, and in looking out for the poor among them were preparing their hearts. The safety and power from on high that was promised was coming, but the onslaught from the outside was also coming, and only those prepared could expect the conditional promise to hold--"if ye are prepared, ye shall not fear" (v. 30).

And how does this preparation come about? Notice the warning and binary language throughout the section. Notice the clarity of blessings for membership, and cursings for all other choices that aren't oriented toward his all-in covenant belonging. Notice that there is a command to physically gather, but that it's coming with promises of power, of a law to be given, of new appointees to be called, and of a new arrangement ordering the "property" of the church.

And notice the parable at the center of it all, teaching those with ears to hear in the same manner the Lord deployed during His earthly ministry. The binarity of not being His unless we are one in Him is the exegetical conclusion drawn from the following text:

What man among you having twelve sons, and is no respecter of them, and they serve him obediently, and he saith unto the one: Be thou clothed in robes and sit thou here; and to the other: Be thou clothed in rags and sit thou there—and looketh upon his sons and saith I am just? Behold, this I have given unto you as a parable, and it is even as I am.

The obvious injustice of rewarding equally faithful sons with unequal material and social position is the valid point to draw from the surface of the parable. But as readers think of how it applies, the facile comparison between the robes and rags and REWARDS breaks down. Robes versus rags describes the initial conditions of current members of the Church. It corresponds not to the end state, but to the starting point God has brought us down to earth with--inequalities abound. The lesson of the parable, and of the unity of the covenant people isn't in how we reward faith--the fairness of our rewards has to be the given here--but in how we erase the inequalities of our initial conditions, in how we flatten "respect of persons."

The problem with group unity is that it only takes one individual to break it definitively. It requires each individual to direct the diversity of strengths each one brings to the benefit of the whole. A single fish swimming to the side makes the school more vulnerable to predators in the water. But if we can obey God's commandments to temporarily sacrifice our means or our pride in our position, and "look to the poor and needy, and administer to their relief that they shall not suffer," He will reward those that seek it with His more permanent riches, perhaps even the earthly ones with which we can see to our own and others' temporal needs.

These saints have no idea what's in store for them. Collectively, they will fail to reestablish Zion. But many will learn lessons and reap eternal rewards that allow the core faithful to continue and grow--like Daniel's stone cut from the mountain without hands--to fill the whole earth. And the work of gathering Zion hasn't diminished or fundamentally changed in principle, only in form. Our task now is to build on these preparatory counsels: love our brothers like ourselves, impart of our substance one to another, grow together by each growing toward Christ. It's the model of the Godhead, and it applies in our marriages, our families, our church congregations, and even in our various polities. To be truly His, we have to be truly one. To be truly His, we have to pledge our all to Him--our will and our property. To be truly His, we have to be willing to allow Him to cut away our drag, whatever that might be, and instead let Him magnify our force to the benefit of the whole. And that might make us new creatures, bring us knowledge of talents we never knew we had, take us places we never thought we'd go. But love will fill us, blessings will accompany us, and no power will prevail against us when we are one, when we are His. He has laws, moral prescriptions, manners of operation, hierarchically organized appointees, physical spaces dedicated for His services, ordinances, and even economic commandments as elements of His Order. He can make more of us than we can make of ourselves, both individually and collectively. All we have to do is let Him use us as His ingredients. All we have to do is let Him cook.

_(2).jpg/800px-Mormon_plan_of_Salvation_diagram_(English)_(2).jpg)